Email Genie: Sentence Transformers 🦾

In the last post, I explored BERT for generating embeddings, but the results were far from ideal. This was most likely due to the messy email data and not being able to fine-tune models since I had no GPU access.

This time, I’m testing out Sentence Transformers, these are models designed specifically for capturing semantic meaning more effectively. They’re lighter, faster, and hopefully a better fit for this project.

Strong embeddings are key to reaching the main goal of this project: classifying emails. Let’s see if Sentence Transformers can finally give me solid enough embeddings to move forward!

Sentence Transformers

So far in this series, I have introduced Transformers with a focus on BERT detailing how it creates embeddings and how those embeddings performed. As a quick recap, BERT creates context-based word-level embeddings which are then pooled to create a single sentence-level embedding.

However, pooling methods (like mean pooling) has limits. All words are treated equally regardless of how much each word contributes to the overall meaning and so, BERT isn’t really suited for tasks like semantic similarity.

Ideally, we’d feed sentence pairs into BERT, fine tune the model and create embeddings that reflect the difference between the sentences. This can take a really long time and doesn’t scale well with large datasets.

This is where Sentence Transformers can help! They’re built on top of BERT and are specifically designed for tasks like semantic similarity. Unlike standard BERT embeddings which are compared after training, Sentence Transformers are fine-tuned during training on sentence pairs to capture differences between sentences.

In the next section, I’ll walk through a diagram to show how Sentence Transformers work and what they output.

How do Sentence Transformers Work

Step 1: Input Sentence Pair

Each input consists of a pair of sentences: sentence A and sentence B.

Note: The model uses a twin network where both sentences are passed separately through the same BERT model meaning the weights are shared between the two inputs.

- For labelled sentence pairs:

The model is fine-tuned by updating BERT’s weights based on the loss calculated from comparing predicted and actual classes. Backpropagation flows from the output, through the feedforward network (FFNN), and all the way back to BERT. This fine-tuning helps BERT learn semantic relationships specific to the dataset.

- For unlabelled sentence pairs (like my project):

I use pre-trained Sentence Transformers where all weights are fixed. These models are trained on large, diverse datasets and have already learned to produce high-quality semantic embeddings. That’s why out-of-the-box Sentence Transformers work much better than out-of-the-box BERT embeddings for tasks like semantic similarity.

Step 2: Pass sentences to BERT

Each sentence is passed separately into the shared BERT model.

BERT returns fixed-length sentence embeddings usually by pooling the token embeddings like discussed in previous post. The embeddings for sentence A and sentence B are noted as a and b.

Step 3: Calculate difference

After creating the two embeddings, the absolute difference between them is calculated. ∣a−b∣

This helps the model understand how similar or different the two sentences are.

Step 4: Concatenate Vectors

Create a combined vector by concatenating:

-

Embedding for sentence A (

a) -

Embedding for sentence B (

b) -

Absolute difference (

∣a−b∣)

Step 5: Pass Through Feedforward Network

Pass the combined vector into a fully connected two-layer feed forward neural network (FFNN).

There are two sets of weights: one connecting the input to the first layer, and another connecting the first layer to the second layer.

These weights transform the combined vector into logits, which are raw confidence scores for each output class.

Step 6: Output Logits

The FFNN outputs a vector of logits, which are real numbers that can be positive or negative and do not sum to 1.

For example:

\[\text{logits} = [1.2,\ 4.5,\ 1.7]\]Each value corresponds to a class:

-

Class 0 (entailment): 1.2

-

Class 1 (neutral): 4.5

-

Class 2 (contradiction): 1.7

These are confidence scores, not probabilities yet.

Step 7: Apply Softmax

The logits are passed through the softmax function, which converts them into probabilities between 0 and 1 that sum to 1.

For example:

[0.05,0.85,0.10]

The class with the highest probability is selected as the model’s prediction. In this example, the prediction is class 1 (neutral), meaning the sentence pair is unrelated.

Here is the description of the output classes:

-

0 = entailment: A supports B

-

1 = neutral: A and B are unrelated

-

2 = contradiction: A contradicts B

Implementing Sentence Transformers

Implementing Sentence Transformers is a lot simpler than working with BERT directly. This is as Sentence Transformers essentially run BERT under the hood, handling the tokenisation, chunking, and pooling. All you need to do is pass the input text and the model takes care of the rest! I followed the HuggingFace tutorial and the process was straightforward. Here are the key steps I took:

Step 1: Initialise model

I used the same model as used in tutorial: ` all-MiniLM-L6-v2`.

Step 2: Pass emails to model and store the embeddings

There is no need to chunk or tokenise the text, .encode does this all for you.

I batched the data to make training quicker and chose to convert the embeddings to a NumPy array to make evaluation easier!

Step 3: Stored the embeddings

I saved the created embeddings so I can access them at later date without having to rerun previous steps to get the embeddings.

Evaluating Embeddings

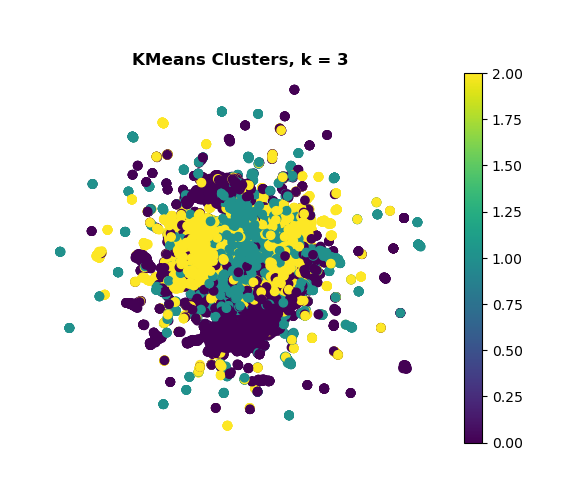

KMeans

There is visible overlap between clusters, suggesting the embeddings are not well separated. This is reflected by a low silhouette score of 0.023 and a high inertia value of approximately 164,000, both indicating weak cluster density and separation.

A key limitation of KMeans is it assumes that all clusters are spherical, which is unlikely for noisy email data such as the Enron dataset. I would expect clusters for emails not to be uniform and have the same size and shape.

While Sentence Transformers generally offer stronger embeddings than traditional BERT, the lack of fine-tuning on this specific dataset may contribute to the weak clustering performance. Given these factors, it would be worth exploring alternative clustering methods that don’t assume spherical clusters.

Assessing KMeans Clusters

To better understand the results, I reviewed example emails from several clusters to assess whether any meaningful themes emerged:

Cluster 0: Operations

This cluster seems to be based around day-to-day operations like scheduling, browser updates and general logistics.

Cluster 1: Legal

These emails deal with formal business contracts, tax forms and documentation. It’s mostly legal or financial in nature, with a focus on compliance and approvals.

Cluster 2: Incident Reports

Emails here are longer and more detailed regarding updates about ongoing issues, projects or internal problems. They include things like repair status, blackout planning, and breakdowns in communication.

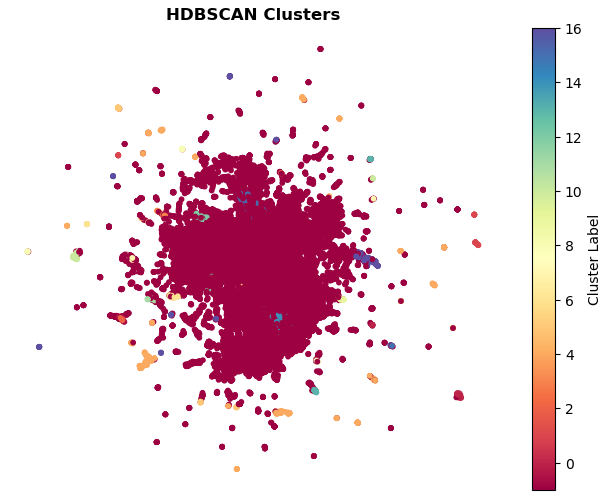

HDBSCAN

The plot shows that HDBSCAN identifies a large set of points as “noise” which suggests that many embeddings are very close to each other and don’t form well-defined groups. I decided to use HDBSCAN instead of DBSCAN since it doesn’t require setting the number of clusters and is better suited for noisy data like Enron dataset.

The clusters that do form appear quite sparse and spread out. Given the relatively high number of clusters, it’s likely that some of these clusters are not particularly meaningful or useful.

Sentence Transformers can struggle with semantics in generic emails especially without fine-tuning. This might explain why many Enron emails, which are often brief, repetitive, or generic, end up classified as noise.

Assessing HDBSCAN Clusters

As with KMeans, I reviewed a sample of emails from each of the clusters.

Note: I ignored the -1 noise cluster and clusters with fewer than 100 emails as I wanted to focus on the most meaningful groups.

Cluster 0: Legal

Contains emails related to formal business documentation and legal agreements, such as ISDA Master Agreements and certification paperwork.

Cluster 4: Operations

Represents operational messages, including shipping or reports on location or status

Cluster 10 Informal

Includes casual communications, internal updates or personal messages with references to timing and travel plans.

Cluster 12 Legal/Finance

Centred around contract management and purchase agreements, highlighting transactional or negotiation communications.

Cluster 14 IT/Tech:

Focuses on technical updates or IT-related messages, such as software upgrades and system requirements.

Cluster 15 Operations:

Contains progress or status updates about operational activities, including repair assessments and resource allocation.

Cluster 16 Tax:

Relates to tax-related communications, specifically regarding tax treaties and jurisdictional considerations.

Results Wrap Up

Overall, there is noticeable overlap between emails across clusters, but this was expected. TF-IDF results had already hinted that emails often touch on multiple general topics. This is a common challenge with email data, where a single message can reference operations, legal matters, and financial details all at once.

Despite this, the clustering results align reasonably well with the initial TF-IDF findings, which suggested three main topic areas: Operations, Legal, and Finance. These themes emerged again in both KMeans and HDBSCAN evaluations, indicating that the Sentence Transformer embeddings are capturing some meaningful structure in the data.

However, the Sentence Transformer model was not fine-tuned on the Enron dataset. As a result, many brief or generic emails—which make up a large portion of the dataset—may not be well-represented in the embedding space. This likely contributed to the large “noise” cluster in HDBSCAN.

It’s important to remember that the UMAP plots used for visualisation may not represent the actual vector space well. The whole purpose of UMAP is to reduce the dimensions of the embeddings, so clusters may be distorted.

Summary

In this post, I used Sentence Transformers to generate embeddings for the Enron emails, which captured meaningful topics like Operations, Legal, and Finance better than previous BERT embeddings.

Clustering with KMeans and HDBSCAN showed some overlaps and a large noise cluster likely due to the model not being fine-tuned on this dataset.

Overall, while the embeddings have their limitations, I thought they provide a reasonable starting point for exploring classification!